REVISITED - Mindfulness in Manhattan: A Walk to Change Perspective

June 2020. We are in the throws of a pandemic, the consequences of which have exposed the innumerable subtle and overt ways in which racism very much still exists within the very fabric of our society. With so many people still out of work or working from home, as they say, “We’ve got time.” And so all over the country, protests in big cities and sleepy towns alike have called out police brutality, medical malpractice, mass incarceration, the celebrated existence of a terrorist group (the kkk), disproportionate funding within communities of need, and on and on down the laundry list of racist institutions. Suddenly, it’s all the rage to say that “Black Lives Matter,” to post a black square in solidarity, to say how sorry you are for all that Black and Brown people have had to and currently have to deal with on a daily basis.

With this resurgence of the Civil Rights Movement, our family has begun talking even more than before about disparities and the existence of racism within our own professions - teaching and photography. So, Dad suggested that I revisit this blog post, which was really the catalyst for what will be a lifetime of examining and taking down racism within my own mind and actions, and within my professional community.

I’ve read this piece a few times now and am struck by how pertinent each question I asked is to my process today, not just while photographing, but also while beginning to engage (for the first time) in political discourse and protest actions. Undoubtedly, this walk and my examination of it have helped me immensely in reframing my attitude towards privilege, bias, action and reform.

[At the time I wrote this in August 2019] Over the weekend I went to an out-of-town concert by myself. Not only that, but this was a “no phones” show (Thanks, Jack White.) Just past security, we all had to put our cell phones in locked pouches which could only be unlocked in certain emergency locations. The purpose? To ensure that everyone be fully present and engaged with the music, not trying to record the best soundbite to share to Instagram. At first, I was a little disconcerted. The prospect of being in a crowd, by myself, with no means of communication was a little unnerving. Even when I’ve traveled by myself I’ve always had my phone on me. Between sets I had nothing to do but observe the people around me, pass time lost in my thoughts, and slyly move through the crowd to get closer to the stage. As I did so, I realized just how much I needed the disconnection. Not from communication entirely, rather from the need to capture and present every facet of my experience.

As someone who brings in the majority of her business from social media, I’ve slowly fallen into the trap of needing to post about each photoshoot, each meal, each little excursion in order to maintain my online presence and build the personality of my brand. But at what point do I then stop enjoying my life for its own sake and start doing things just for attention?

This played a major part in examining what to post on Instagram about my involvement in Asheville’s vigils and march. The answer? Nothing. At least, nothing at the time. What selfie, photo of a sign that wasn’t mine, or unapproved video of a speech would be anything but virtue signaling coming from me - a straight, white woman who has remained largely a-political online until more recently?

“At what point do I then stop enjoying my life for its own sake and start doing things just for attention?”

Traveling, in particular, has time and again led me to that question. Did I order that steak tartare in France just for the ‘Gram or do I actually want to eat it? (Tartare makes for terrible photos but is, in fact, delicious. Next question, please.) Did I rent a car and drive through Northern Spain for a good story? (Yes, but if the primary aim was to swap amusing stories with my well-traveled grandparents then no harm done.) Did I stay up till 3am sharing my blog posts to my Instagram story while in Ireland with my family rather than resting up to enjoy another full day? (Yes, and boy could I have used that sleep.)

When Dad and I went to Manhattan for a day in July, spending our afternoon walking the 160 blocks from Penn Station to the Cloisters, I was able to take that question one step further: even in a public sphere (where photographing is technically legal), when is it time to put the camera away not only to be more present myself, but to allow my prospective subjects to maintain their privacy?

Again, this question has been incredibly helpful in my examination of if and how to document the protest. I’ll talk much more in depth about this in my next article.

In my business work it’s fairly cut and dry - my clients come to me wanting photos and so I provide them. Occasionally I will have moments when I exercise discretion - a bride needing a moment to mourn a departed loved one, for instance. These raw, emotional photos are coveted among the masses of photographers and garner enormous attention within our Facebook groups, but (if the couple is not expressly comfortable with this situation) at what cost? Surely, privacy in grief, particularly on such a monumental day, comes first. Does this not also translate into street photography? Especially in regards to anonymity during civil unrest.

[Not at all rhetorical, I still haven’t landed on a precise answer here. My solution for now is to use these questions as a guide to address each potential photo individually. That may sound like overkill, because if I sit and stare at a situation running through each question then likely the photo opportunity will have already passed. But, just like any skill practiced thousands of times, the process has now become so intuitive that I’ve learned to address these questions in a matter of milliseconds.]

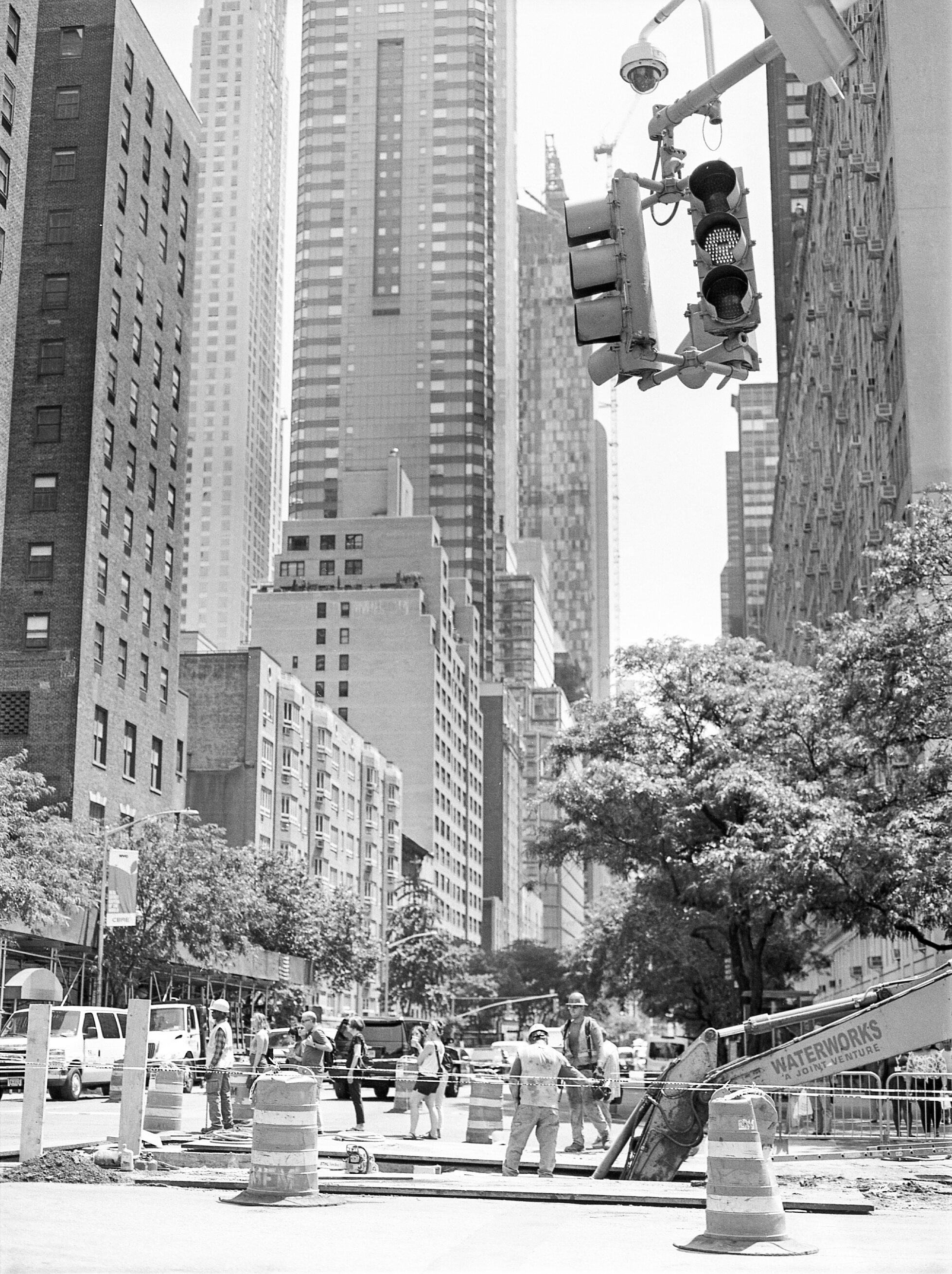

When we set off at 33rd I thought nothing of it. I had 5 rolls of film with me and I intended to use them all. I went through the first one quickly as we walked through Central Park, delighting in the high contrast provided by the beating sun.

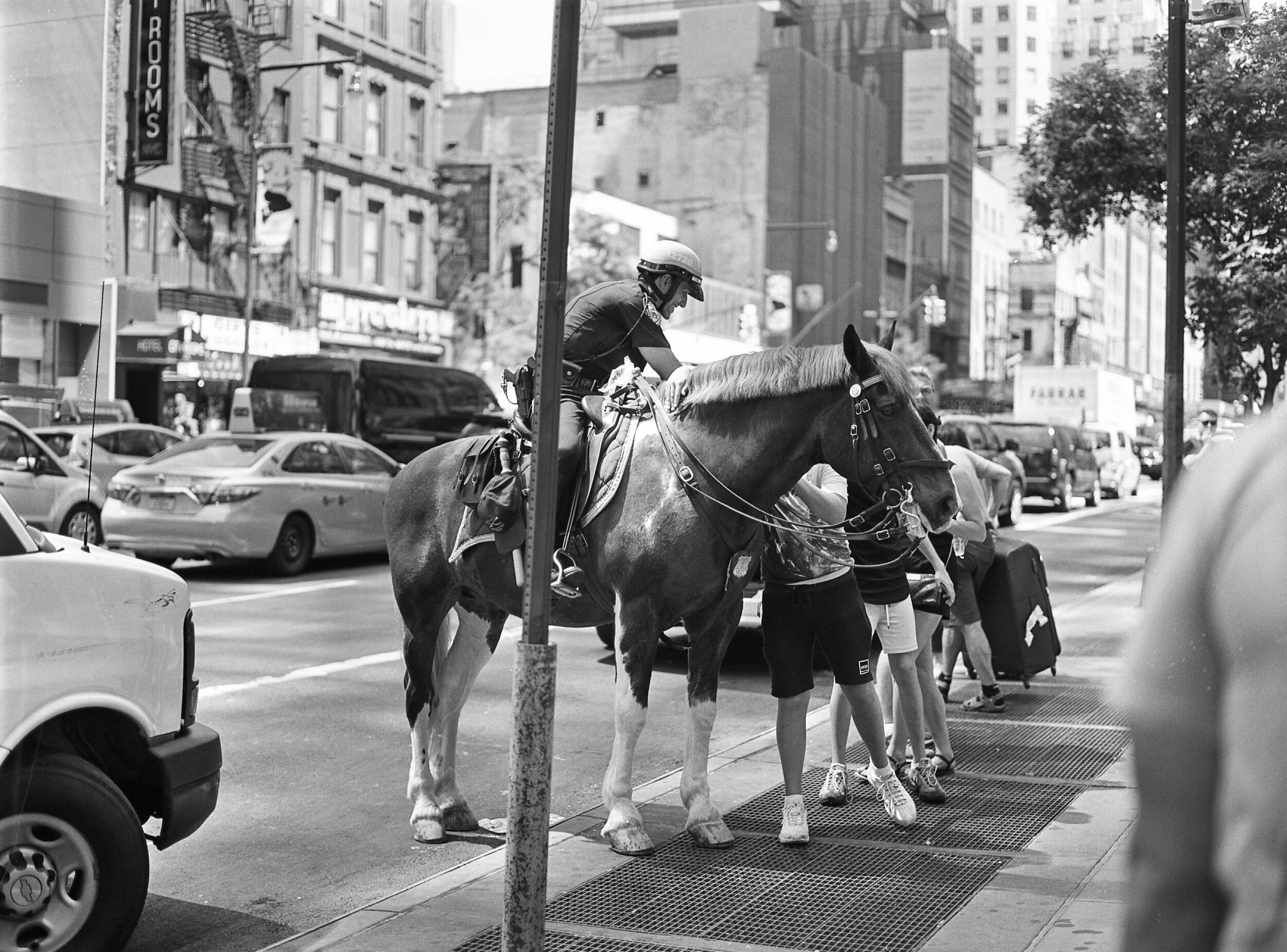

I wound my third roll - now expired color - as we entered Harlem, easily rolling the film while we kept walking. I noticed some strange looks, but that’s not uncommon. I can’t fault anyone for thinking it a bit odd, even uncomfortable, for a random stranger on the street to be taking another stranger’s picture, especially with my bulky 645.

Again, I’m a young, white, fairly well-dressed female who doesn’t present as menacing, likely more as naive or clueless, essentially harmless other than my desire for photographic exploitation. A tourist who’s here for the ‘Gram. Passersby wouldn’t know I have a degree in photojournalism, a blog examining the ethics of my practice, and a conscience. That’s how judgement and bias works. The difference is that I can lean into this misconception to get the photos I want without being stopped. Not so with less privileged people.

Just a few blocks down Amsterdam Ave. I started to notice something: Dad and I were the only white people. For the first time in my life I was the minority, and I would be lying if I said it didn’t disconcert me. I have always made an effort to ensure that my travels are educational as well as pleasurable. Lately, I have dwelled on how to use my platform for positive change, how I can be an ally and aid in inclusion and representation for marginalized groups - whether people of color, those within the LGBT community, women in general. I am a straight, white woman who has enjoyed a fair amount of privilege, and so I’ve been self-conscious about vocalizing this need for inclusion. Not because I don’t wholeheartedly believe in equality, but for fear of seeming hypocritical. How can I profess to know how someone who has grown up oppressed, outcast or maligned feels? But fear of social criticism is no reason to stay silent and so this year I’ve started exploring how I can best use my own resources and knowledge to help those underserved. It seems that first, before any potential savior complex could get in the way, the Universe knew I needed a lesson in humility.

In my original post I left out a key piece of information: that midway through Harlem, right about the point where we realized we were the only white people save for one construction worker (who was watching us intently), we passed by a man who seemed rather unhinged and more than a little hostile. The next few moments happened in such a blur that I don’t remember the full exchange, but after making eye contact and nodding at him (our typical street salutation), the guy - who was already muttering - turned around and started yelling death threats at Dad. We kept walking and eventually the guy turned his attention elsewhere, but it was a wholly unnerving experience. I left this story out of my original article because the man was Black, and it seemed rather counterproductive to paint a maligned neighborhood and a maligned group of people in the same light as the untrue stereotypes which keep them oppressed. However, I think it’s important to share now that part of this experience wasn’t just feeling other, it was being physically threatened. This was a wake up call more than anything else, to be so completely unwelcomed (the construction workers watched this happen and said nothing) just based on the color of our skin (an assumption, that he judged us as oppressors) that our lives were in danger. We experienced this once, while actively seeking out a place we’d never been. Imagine having to endure that on a daily basis while simply going about your everyday life.

As we walked the next couple of blocks, I saw several vignettes and quite a few people that I would’ve liked to photograph. But, for the first time in a while, I questioned myself. Why did I want to photograph each person - what made them seem interesting? What if they got mad at me? In publishing their images, would I be taking something away from them?

Therein lies the crux of the question: In walking into someone else’s community (and here I mean any community in which I am not expressly invited) - their safe space - and capturing their likeness through my own personal voice (and therefore bias) am I unintentionally taking away from their ability to tell their own narrative?

My intention when photographing strangers is to celebrate - identity, community, our differences. But, well-intentioned that I may be, is it still arrogant to walk into someone else’s community and begin creating art which will still be used in part to promote my own business? More over, in this era when racial tensions are high and prejudice runs rampant (I say “in this era”, but has it ever been any different?), could my voyeurism be misconstrued as an attempt to divide? As I am the outsider in this equation, I don’t know that I get to answer that question. I don’t get to tell someone that I did not, in fact, make them uncomfortable if they’ve told me I have.

So, I put the camera away. In part for the reasons above, and in part also because I wanted to internalize this experience of being “other” so I could better understand how others might feel.

Eventually, we turned off of Amsterdam into Broadway to head towards the Cloisters and I picked my camera back up. This time harkening back to my senior research paper where I spent 25 pages examining how photographs can be manipulated along every step of the process and therefore why we as photographers have the responsibility to evaluate what messages our photos are sending and how they may affect people. Particularly in the realms of social justice and cultural equality.

I’ve written this segment in fits and starts because I don’t want it to come off as a humblebrag or something. I am quite often quiet about my political opinions because I have a difficult time verbally articulating them; I’m much more coherent in writing when I can actually organize my thoughts. So this segment is an attempt to open up the dialogue both with myself and those who follow me online as I continue to explore the social, ethical and personal impacts of my photography.

So much has changed in the year since I wrote this piece. To be honest, I’m proud of this article and for beginning the work when I did of examining and discussing internalized racism. I’m proud of the conversations I’ve had for years with friends and exes alike about how racism is still a part of our framework today and how we benefit. I’m proud that I’ve gotten to work with such a diverse range of clients, to learn about their cultures and experiences in such an intimate and personal way. I’m proud of the work I’ve done in my after school program and my volunteer photography work to give underrepresented and underserved students a voice, and give them the tools to use their own. But this walk showed me that there is still so much more work that I can do. Beginning with examining how I myself - even unconsciously - contribute to problematic practices whether in photography or otherwise. The fight against institutional racism doesn’t stop when brands start using #BLM to signify their wokeness. It ends when we all - the white peoples benefiting from the system - examine our shortcomings and do what must be done, likely including a full paradigm shift, to ensure all are truly and finally equal.